Road to Carbon Neutrality

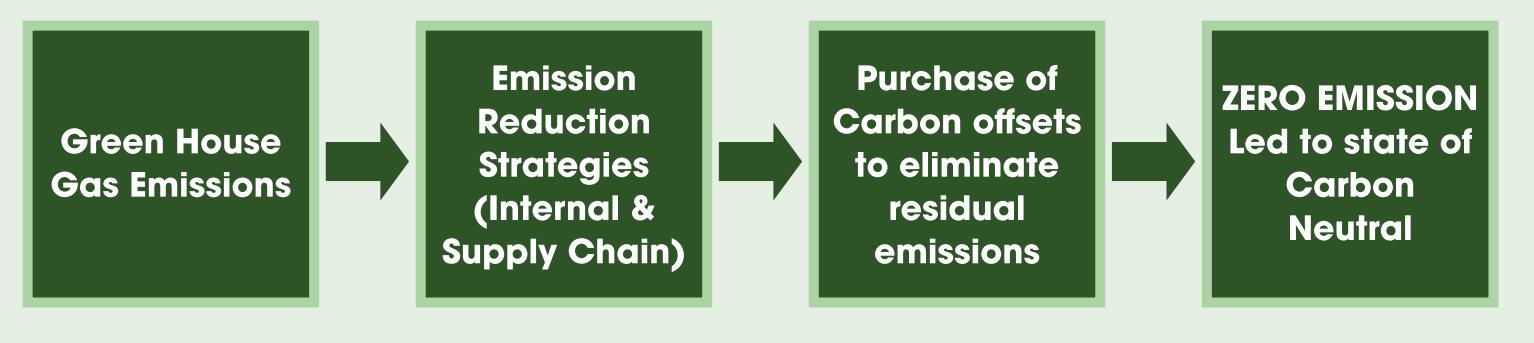

The internal emissions reduction strategies include:

∅ Inventory of GHG emissions.

∅ Implementing internal mitigation strategies aligns with global goals to reduce CO2 emissions by half by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. Steps include:

∅ Investing in low-carbon capital projects,

∅ Shifting to lower-emitting equipment, materials, and fuels,

∅ Investing in energy efficiency measures and renewable onsite power.

Emission reduction strategies for the supply chain include:

∅ Estimate supply chain emissions,

∅ Estimate emissions embedded in the products,

∅ Implement mitigation strategies such as:

∅ Choosing low GHG emitting suppliers.

∅ Incentivizing suppliers to reduce GHG emissions.

∅ Re-designing products and services to reduce the GHG footprint.

The final step in the emissions reduction initiative is to purchase carbon offset credits to eliminate any residual emissions from the direct (scope-1) and indirect (scope-2 & 3) sources.

Understanding Carbon Offsets

∅ Switching to renewable energy development from conventional power generation, thus ending fossil-fuel emissions,

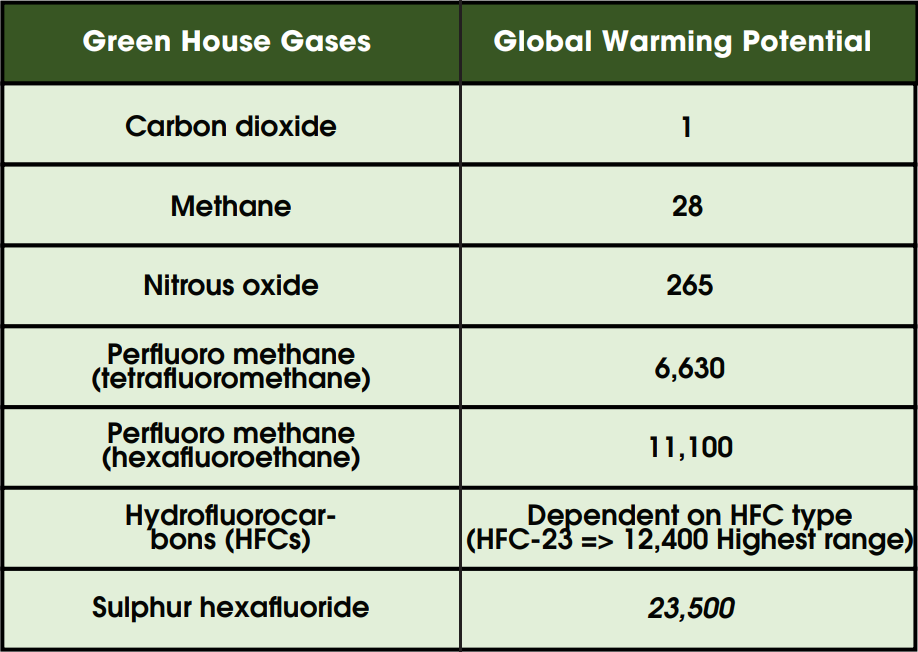

∅ Capture of highly potent GHGs like methane, N2O, or HFCs,

∅ Avoiding deforestation.

∅ Develop standards and criteria to set the quality of carbon offset credits.

∅ Review offsets projects against standards with the help of third-party verifiers.

∅ Maintain registry systems to keep records of issues, transfers, and retirement of offset credits.

∅ The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), and

∅ Joint Implementation (JI).

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) is part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It offers the opportunity to purchase carbon credits from offset projects in low- or middle-income nations to high-income countries’ public and private sectors.

The CDM advances the sustainable development agenda in the host country. CDM projects generated emissions credits called Certified Emission Reductions (CERs), which are bought and traded. Joint Implementation operates in developed countries, and tradable units from JI projects are called Emissions Reduction Units (ERUs).

Criteria for a high-quality carbon offset

The carbon offset scheme can be considered high-quality only if the following characteristics are there, such as:

∅ Additionality: In the context of emission reduction projects, the additionality of a project means that the only way the Project exists is because of the funding from carbon credits.

In other words, emission reductions or removals from a mitigation activity are additional if the mitigation activity has yet to take place without the added incentive created by the carbon credits.

∅ Permanent or permanent: Sequestration projects need to ensure that emissions are kept out of the atmosphere for a reasonable length of time. The longer the guarantee, the higher the relative quality of the offset credits.

∅ Not claimed by another entity.

∅ Not associated with significant social or environmental harms.

Road to address the Paris Agreement objectives.

Post the Paris Agreement, countries, regions, cities, and companies must invest in technology and capacity building to meet carbon-neutral targets and zero-carbon solutions.

In the race to limit global warming below or up to 1.5 degrees centigrade, Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) can play a vital role. The Carbon Capture and Storage technology prevents the release of carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere by capturing CO2 produced during the industrial production process, compressing it for transportation, and injecting it in carefully selected secure and deep geological sites for permanent storage. The technology has been used in industrial settings to purify natural gas, hydrogen, and other gases since 1930.

However, in 1972, the technology was used commercially for the first time for carbon capture and storage purposes. As of 2019, there were only 19 large-scale CCS projects in operation; however, the number is expected to grow to more than 2000 large-scale CCS plants across the globe. In addition to shifting to bioenergy or biofuel for energy production, CCS technology is expected to be one of the most effective technologies to combat the climate change challenge.

Hence, we must mobilize enormous capital into climate mitigation technologies. A conservative estimate shows that by transitioning to a low-carbon economy, we can gain about US$ 26 trillion in direct economic benefit globally by 2030. For example, In 2017, about US$280 billion was invested in renewable energy projects.

Recognizing new investment opportunities in climate-related projects, capital markets worldwide are bullish about this sector, and more than 160 financial firms, with a value of US$86 trillion in assets, have shown commitment to accept the TCFD’s recommendations.

The biggest challenge to addressing the Paris Agreement goals is that we need to increase the production of renewable energy at least nine-fold, for which we need to accelerate the development of clean energy infrastructure and significant amounts of land for onshore wind and large-scale solar installations.

Nonetheless, globally, we are fortunate enough to have enough altered land for agriculture, infrastructure, and other development activities, which can be used for dual purposes or reused for renewable energy development purposes.

We are estimated to have more than 600 million hectares of land available globally, or approximately 17 times more land than we require for renewable energy infrastructure. This land bank includes both the highest greenhouse-emitting countries and others.

In developing clean energy infrastructure, it is essential to ensure we avoid committing the same mistakes, undermining the environmental and social impact of land use, as we have committed during the development of the fossil fuel sector. We must look for low-impact pathways for renewable energy infrastructure build-up.

A report published by The Nature Conservancy prescribed six pathways to a green energy build-up:

∅ Identify and approve low-environmental impact zones for renewable energy development.

∅ Develop renewable energy plants and transmission with a low impact on wildlife and habitats.

∅ Develop science-based guidelines and standards for green energy plant developers and lenders on identifying or what constitutes low-impact project siting and design.

∅ Incentivize the development of renewable energy projects in brownfields (former closed mine sites, former industrial sites, already contaminated unusable and degraded lands) over greenfield sites.

∅ To make buying low-impact renewable energy a corporate commitment to address their sustainability goals (social equity, environmental consideration, and financial profit) for both climate and nature.

∅ Incorporate environmental and social performance standards into financial institutions’ lending criteria to ensure renewable energy investments are undertaken in low-impact zones and avoid impacts to nature and communities.

Hence, to combat climate change, both for adaptation and mitigation, we require green technology and infrastructure and new financial instruments in the form of sustainable finance.

Sustainable Finance: To finance the future

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement are the two most urgent global commitments we must address by 2030 and beyond. However, we need technology and finance to speed up the transition towards a sustainable economy.

An estimate of the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) mentioned that globally, we need to invest about US $ 5 to 7 trillion a year in infrastructure, clean energy technology, water, and sanitation to meet SDGs and Paris Agreement objectives.

As a result, banks, insurers, and investors across the globe have pledged to integrate sustainability into their operations. It is estimated that the global market for sustainable finance has grown manifold from USD 11.3 billion in 2013 to USD 183 billion in 2018. Hence, sustainable finance will play a vital role, alongside sustainable technology, in accelerating the transition towards a sustainable global economy.

What is Sustainable Finance?

The genesis of sustainable finance can be traced back to the 1980’s-1990’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) movement. However, CSR is considered to be a philanthropic activity of corporations; it is not integrated into a company’s business model. With the growing stakeholder, institutional, and regularity pressures, sustainability aspects have gradually been integrated into business practices, and embracing sustainability is now seen as a factor for competitive advantage.

In 1992, the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) was set up, and in the same year, the Convention on Biological Diversity was organized.

Since the 2000s, many international frameworks have been published, such as

∅ the Equator Principles (2003),

∅ Principles of Responsible Investment (2006),

∅ Principles for Sustainable Insurance (2012),

∅ UNEP Inquiry into a Sustainable Financial System (2014),

∅ Addis Ababa Action Agenda,

∅ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (2015),

∅ the Paris Agreement on Climate Change (2015).

Following the publication of these frameworks, policymakers and regulators have focused on developing sustainable finance markets.

For example, some of the initiatives are:

∅ Issue of Climate Awareness Bond by the European Union in 2007,

∅ Issue of the first Green Bond in 2008 by the World Bank,

∅ Task Force on Climate-related Disclosures (TCFD) in 2015,

∅ The Chinese Green Bond Project catalogue in 2015,

∅ French Energy Transition Law and Article 173 in 2015,

∅ The Network for Greening for Financial Systems (NGFS) in 2017,

∅ The EU Action Plan on Sustainable Finance in 2018,

∅ The Principle for Responsible Banking in 2019,

∅ EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities (2020),

∅ Finance for Biodiversity Pledge (2020)

Why Sustainable Finance and Key Elements of Sustainable Finance?

The finance sector has an essential catalytic role in addressing economic, social, and environmental challenges. It can influence the future of business decision processes and business operations. It can motivate investors to embed holistic sustainability values in new investments.

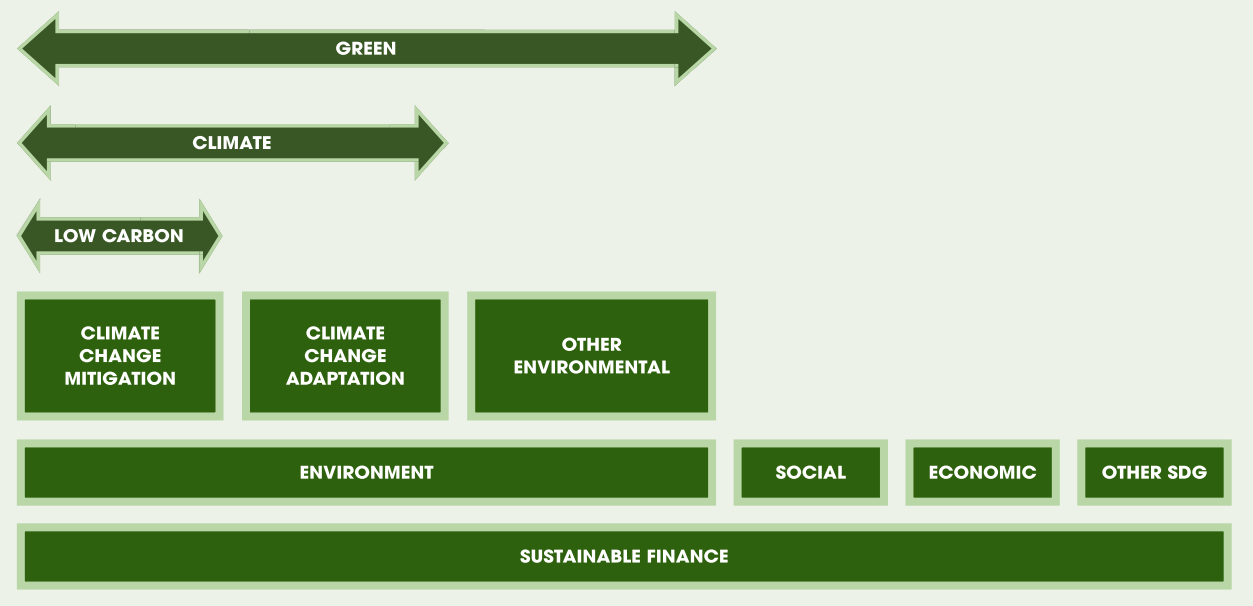

Figure 3: The Anatomy of Sustainable Finance

The Finance sector encourages potential borrowers to present their social and environmental risks and impact assessments before approving their loan proposals. Sustainable finance will reduce the risk of loss, strengthen brand reputations, support the transition to a low-carbon economy, meet stakeholders’ and regulators’ expectations, and facilitate the advancement of sustainable development goals.

Sustainable finance provides desired financial returns and positive social and environmental outcomes, where both traditional finance and investment (primarily focus on financial performance) and ethical or philanthropic donation operate at a sub-optimal level (only focusing on social and environmental performance).

Sustainable Finance has four key elements:

1) Finance focuses on expected returns and associated risks.

2) Governance focuses on systems, processes, and oversights that ensure an organization and its products deliver on its financial, social, and environmental goals.

3) Social focuses on the positive social impact of investments.

4) Environmental focuses on green investment, such as investment in climate change mitigation, investments in adaptation to the physical impacts of climate change, and investments in biodiversity conservation.

Four key components of Sustainable Finance Framework

Over the decades, several initiatives have been undertaken to develop systems and markets for sustainable finance.

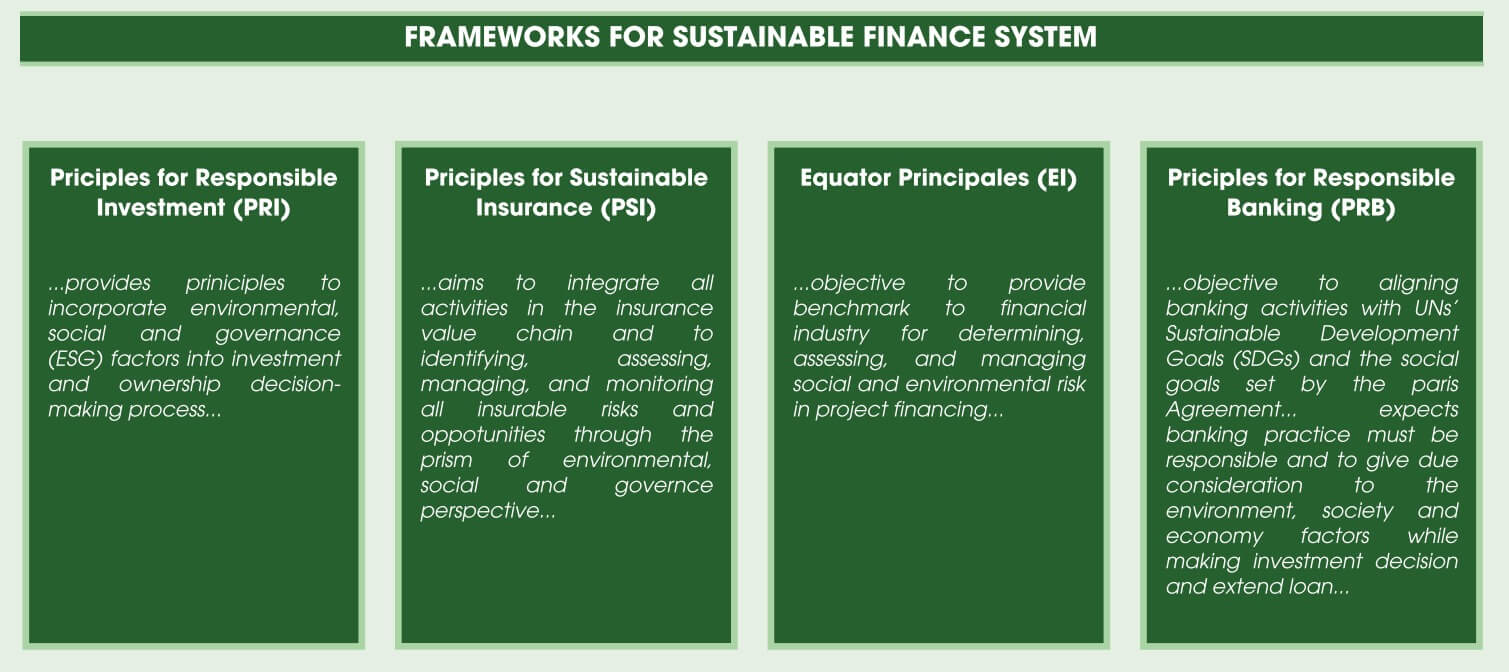

The Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), Principles for Sustainable Insurance (PSI), Equator Principles (EI), and Principles for Responsible Banking are four fundamental pillars of the sustainable finance ecosystem.

The PRI is a framework for the institutional investment industry, including insurance and non-insurance institutions (e.g., insurance companies, pension funds, government reserve funds, foundations, endowments, depository organizations, and investment management companies).

The six Principles for Responsible Investment are:

1 To incorporate ESG issues into investment analysis and decision-making processes.

2 To be active owners and incorporate ESG issues into policies and practices.

3. To Seek appropriate disclosure on ESG issues by the entity’s investment.

4. To Promote acceptance and implementation of the Principles within the investment industry.

5. To work together to enhance our effectiveness in implementing the principles.

6. To report on our activities and progress towards implementing the principles.

To advance sustainable investment policies and regulations in any jurisdiction, policymakers need to define five areas in their policy documents:

∅ Corporate ESG Disclosures define the issuer’s obligation to publish relevant corporate strategies, operations, and performance on key ESG issues so that investors get material ESG performance information on the investee’s investment proposal before making investment decisions and lending engagement.

The prescribed regulatory guidelines on corporate ESG disclosures need to be aligned with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations.

∅ Stewardship is the long-term value of economic, social, and environmental assets on which returns and clients’ and beneficiaries’ interests depend

∅ Investor ESG Regulations demand better ESG disclosures so that disclosing and incorporating ESG information in decision-making becomes a fiduciary duty and obligation of the asset owners and investment managers.

∅ Taxonomies creating a common language between investors, issuers, project promoters, and policymakers so that investors can assess whether a particular economic activity is environmentally and socially sustainable (e.g., what constitutes green or sustainable activities or projects or helps to measure the level of sustainability of investments), whether projects follow robust ESG standards and have the potential to navigate the transition to a low-carbon, inclusive, sustainable economy.

∅ National Sustainable Strategies prescribing a framework so that the financial sector transits towards or supports goals of sustainable and inclusive growth by aligning economic and financial goals with the Paris Agreement and the SDGs.

Figure-4: Four Governing Frameworks for Sustainable Finance System

Sustainable insurance aims to integrate all activities in the insurance value chain and to identify, assess, manage, and monitor all insurable risks and opportunities through the prism of the environmental, social, and governance perspectives. The PSI Principles are a framework for the insurance industry.

Principles for Sustainable Insurance has four principles:

∅ To embed environmental, social, and governance issues in decision-making relevant to business (including company strategy, risk management, underwriting, product and service development, chain management, sales and marketing, and investment.

∅ To work with insurance clients and business partners to raise awareness of environmental, social, and governance issues, manage risk, and develop solutions (including client suppliers, insurers, reinsurers, and intermediaries).

∅ To work with governments, regulators, and other key stakeholders to promote widespread societal action on environmental, social, and governance issues.

∅ To demonstrate accountability and Transparency by regularly and publicly disclosing insurance companies’ progress in implementing the Principles.

The Equator Principles apply to financial products relating to all industry sectors, such as project finance advisory services, project finance, project-related corporate loans, bridge loans, project-related refinance, and project-related acquisition finance. Equator Principles apply to any projects whose capital cost is US$10 million or more.

Equator Principles has ten principles.

1. Review & Categorisation – Review and categorize projects into three categories, A, B, C, based on the magnitude of potential impacts and risks, following the environmental and social screening criteria of the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

∅ Category A: Projects have potentially significant adverse social or environmental impacts that are diverse, irreversible, or unprecedented.

∅ Category B: Projects have potentially limited adverse social or environmental impacts that are few, generally site-specific, reversible, and readily addressed through mitigation measures and

∅ Category C: Projects have minimal or no social or environmental impacts.

2. E&S Assessment where the borrower must conduct a Social and Environmental Assessment of the Project and propose mitigation and management measures relevant and appropriate to the nature and scale of the proposed Project.

3. Applicable E&S Standards- need to apply IFC Performance Standards and Industry Specific EHS Guidelines.

4. E&S Management System & EP Action Plan- establish a Social and Environmental Management System that addresses the management of impacts, risks, and corrective actions required to comply with the applicable host country’s social and environmental laws and regulations.

5. Stakeholder Engagement- The borrower or third-party expert must consult with the affected communities of the Project in a structured and culturally appropriate manner, and the Project must adequately incorporate any affected communities’ concerns.

6. Grievance Mechanism- The borrower must inform any affected communities about the mechanism during its community engagement process and ensure that the mechanism addresses concerns promptly and transparently, in a culturally appropriate manner, and is readily accessible to all segments of the affected communities.

7. Independent Review- An independent social or environmental expert not directly associated with the borrower will review the Assessment.

8. Covenants- An essential strength of the Principles is the incorporation of covenants linked to compliance. Where a borrower is not in compliance with its social and environmental covenants, EPFIs will work with the borrower to bring it back into compliance to the extent feasible. If the borrower fails to re-establish compliance within an agreed grace period, EPFIs reserve the right to exercise remedies as they consider appropriate.

9. Independent Monitoring & Reporting require the appointment of an independent environmental and social expert or require that the borrower retain qualified and experienced external experts to verify its monitoring information, which would be shared with EPFIs.

10. Reporting & Transparency- commits to publicly reporting annually about its Equator Principles implementation processes and experience, considering appropriate confidentiality considerations.

Hence, the banking industry is becoming more aware of the environmental issues. The banking industry also recognizes that they are laggard when it comes to its own human resource policies, as the banking industry has traditionally under-represented minorities, notably women and ethnic minorities.

Considering these factors, in 2019, UNEP FI launched the Principles for Responsible Banking to align banking activities with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the social goals set by the Paris Agreement.

Under the PRB framework, signatory banks are required to contribute towards social goals and report on positive and negative impacts on society and the environment through the banking business. PRB expects banking practice to be responsible and consider the environment, society, and economic factors while making investment decisions and extending loans.

The Principles for Responsible Banking (PRB) are as follows:

∅ Principle 1 Alignment: Align business strategies to individual needs and social goals set in the SDGs and the Paris Agreement and contribute to them.

∅ Principle 2 Impact & Target setting: Evaluate the increase in positive and decrease in negative impacts caused by banking operations and set and publish targets for that purpose.

∅ Principle 3 Clients & Customers: Work with customers to encourage sustainable practices and enable economic activity with shared prosperity for current and future generations.

∅ Principle 4 Stakeholders: Actively work with relevant stakeholders to further promote the objectives of the principles.

∅ Principle 5 Governance & Culture: Carry out commitments to these rules through effective governance and corporate culture as a responsible bank.

∅ Principle 6 Transparency & Accountability: Appropriately review the implementation of these principles to remain transparent and accountable for positive and negative impacts.

Sustainable Finance Product Categories:

1) Sustainable Bonds (Green, Social, and Sustainability Bonds).

3) Sustainability Equity and Index Funds.

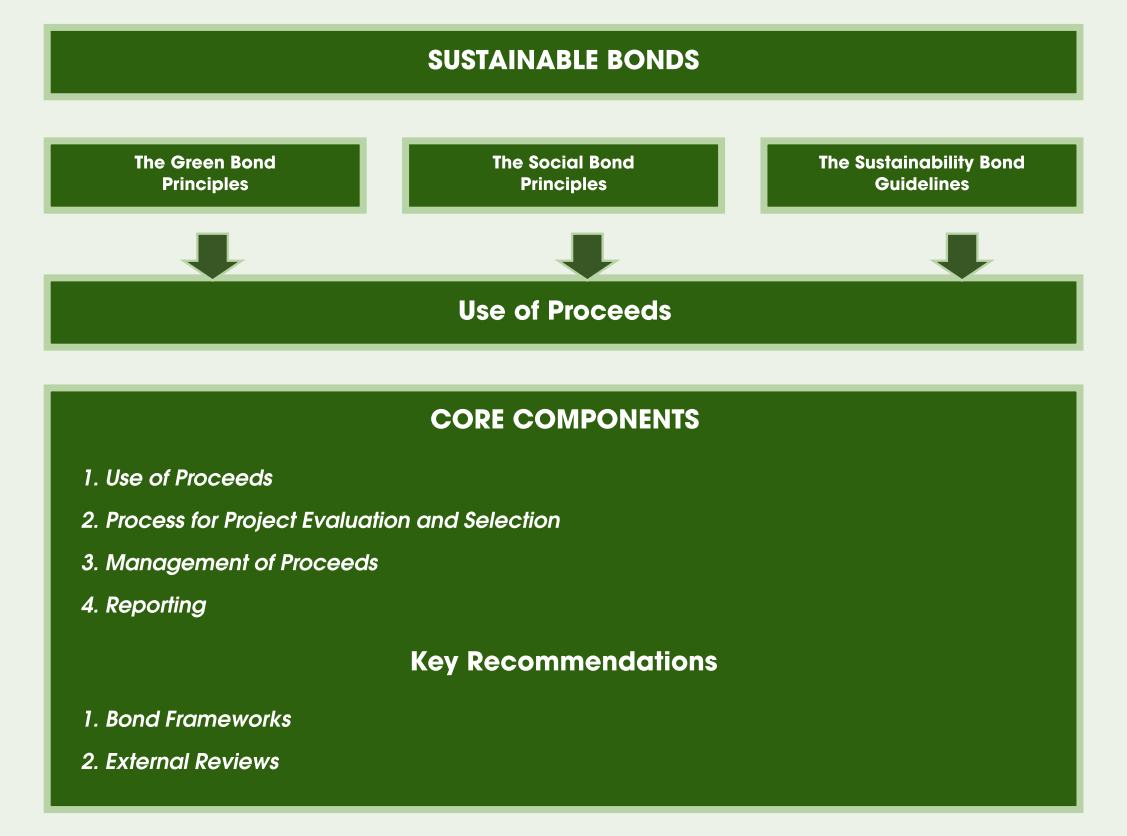

Sustainable Bonds are tradable debt instruments with specific risk, interest, and maturity. Sustainable bonds are mainly categorized as green, social, and sustainability bonds. In addition, there are further subcategories: Blue Bonds (focusing on marine conservation) and transition bonds (to finance transition to low carbon transition). Sustainable loans are provided by banks and borrowers and are supposed to be used to fund green projects as specified and defined in the lender’s Green Loan Framework.

Collectively, these frameworks are called the ‘Principles’. As of 2020, the total value of sustainable bond issuance is USD 594 billion, and 97% of all sustainable bonds issued globally are aligned with GBP, SBP, SBG, and SLBP.

Green Bonds are any bond instrument where the proceeds will be exclusively applied to finance or refinance projects with clear environmental benefits and which are aligned with the Core Components of the GBP.

Eligible Green Project categories include renewable energy, energy efficiency, pollution prevention and control, environmentally sustainable management of living natural resources and land use, terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity conservation, clean transportation, sustainable water and wastewater management, climate change adaptation, the circular economy and or eco-efficient projects, and Green buildings.

Social Bonds finance projects that directly aim to address or mitigate a specific social issue and or seek to achieve positive social outcomes, especially but not exclusively for a target population(s), and are aligned with the Core Components of the SBP.

Social Project categories include providing and or promoting affordable basic infrastructure, access to essential services, affordable housing, employment generation, food security, or socioeconomic advancement and empowerment.

Sustainability Bonds are any bond instrument where the proceeds will be exclusively applied to finance or refinance a combination of Green and Social Projects and which are aligned with the Core Components of the GBP and SBP.

Sustainability-linked bonds are any bond instrument for which the financial and or structural characteristics (i.e., coupon, maturity, or repayment amount) can vary depending on whether the issuer achieves predefined Sustainability/Environmental and or Social and or Governance (ESG) objectives within a predefined timeline, and which are aligned with the Core Components on the SLBP.

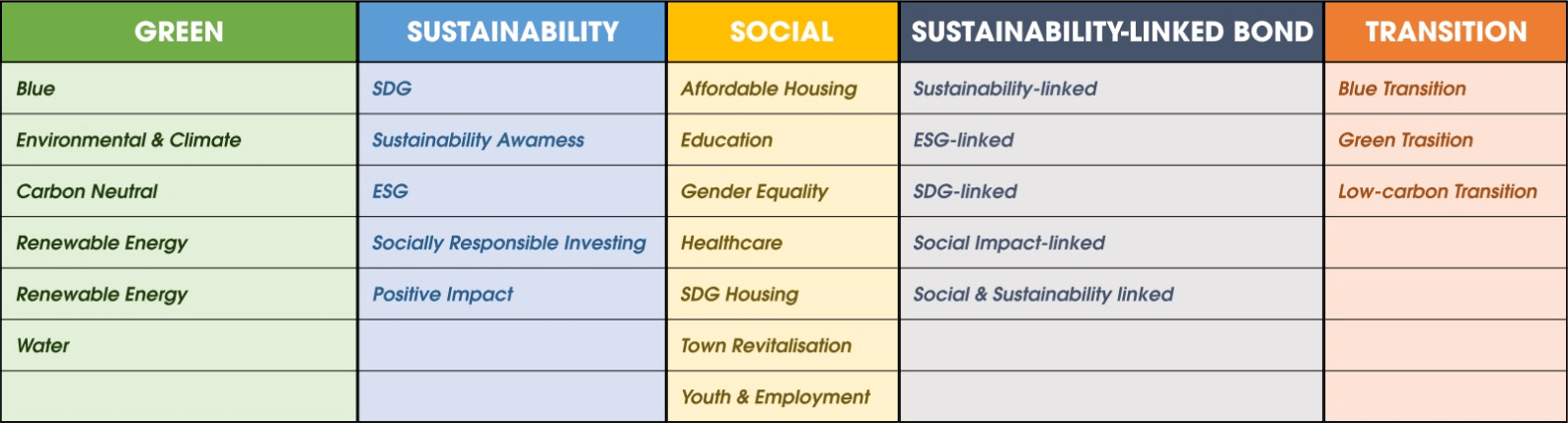

Figure-5: Types & Components of Sustainable Bonds

It is possible to combine a “use of proceeds” approach with a Sustainability-Linked Bond approach if an issuer chooses to earmark the proceeds of their sustainability-linked bond to specific projects, and where these are eligible green and or social projects, by aligning their bonds simultaneously with all the Core Components of the GBP/SBP/SLBP.

Green, Social, Sustainability, and Sustainability-Linked Bonds are regulated instruments subject to the same capital market and financial regulation as other listed fixed-income securities. Subject to any applicable law or regulation, all types of issuers in the debt capital markets can issue a Green, Social, Sustainability, or Sustainability-Linked Bond as long as it is aligned with the Core Components of the GBP/ SBP/SLBP.

Use of Proceeds – Utilisation of the bond proceeds for eligible Green or Social Projects should be appropriately described in the security’s legal documentation. All or a proportion of the proceeds may be used for refinancing. In short, a legal document states that the use of proceeds’ is utilized for green or social benefits.

Process for Project Evaluation and Selection – the issuer of a Green or Social Bond should communicate to investors:

∅ The environmental or social sustainability objectives of the Projects The process by which the issuer determines how the projects fit within the eligible Green or Social Project categories and

∅ Complementary information on the processes by which the issuer identifies and manages perceived social and environmental risks associated with the relevant Project (s)

Management of Proceeds –The net proceeds of the Green or Social Bond, or an amount equal to these net proceeds, should be credited to a sub-account, moved to a sub-portfolio, or otherwise appropriately tracked by the issuer, and attested to by the issuer in a formal internal process linked to the issuer’s lending and investment operations for eligible Green or Social Projects.

So long as the Green or Social Bond is outstanding, the balance of the tracked net proceeds should be periodically adjusted to match allocations to eligible Green or Social Projects made during that period. The issuer should inform investors of the intended types of temporary placement for the balance of unallocated net proceeds.

Reporting – Issuers should make and keep readily available, up-to-date information on the use of proceeds to be renewed annually until total allocation and on a timely basis in case of material developments. The annual report should include a list of the projects to which Green or Social Bond proceeds have been allocated and a brief description of the projects, the amounts allocated, and their expected impact.

Sustainable Finance Investor Strategies and Approaches

Sustainable finance products or assets promise long-term sustainable returns after considering environmental, social, and governance factors. At the same time, investors in sustainable assets expect that the companies they are investing in will be agents of social change, have strong corporate governance, improve environmental and social performance, and ensure the financial implications of sustainability-related issues are taken care of.

Hence, investing in sustainable finance requires strategy. Investment decision-making is itself a complex process. Therefore, the question is, what decision-making process should be taken to select and reject an asset as a sustainable asset or how can investors consider social and environmental issues in their investment decision-making?

Four sustainable finance investor strategies and three additional approaches to sustainable finance investment decision-making exist.

Four sustainable finance investor strategies:

Exclusionary or Negative screening: The investor excludes or rejects certain investments or funds (these can be from specific sectors, companies, countries, or issues) from portfolios based on values, norms, or moral principles. The process can exclude products and services such as gambling, adult entertainment, weapons, and tobacco. Alternatively, company practices involving animal testing, human rights violations, and corruption.

Best-in-class investment: Select investment in those sectors, companies, and countries that lead their peer groups regarding sustainability performance or have positive ESG performance.

Norms-based investment: Exclude investment in companies or government debts that fail to abide by standards set by the UN Global Compact, the Kyoto Protocol, the UN Declaration of Human Rights, or the International Labour Organisation.

Thematic Investment: Investing in companies or assets that contribute and advance sustainable solutions such as green technologies, sustainable agriculture, green buildings, and gender equity diversity).

Additional approaches are:

ESG integration: Investment managers systematically and explicitly include environmental, social, and governance factors in financial analysis. The process focuses on assessing the potential positive and negative financial impacts of ESG issues and incorporating these data in valuing and assessing a company or asset.

Governance impact and active ownership: Investors or shareholders actively engage with senior management to highlight specific sustainability issues and to encourage companies to improve their sustainability issues and policies.

Impact investment: The Global Impact Investing Network defines impact investment as “investments made into companies, organizations, and funds to generate social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.”

In other words, it provides capital to those companies or projects with clear social or environmental goals or intentions for the community well-being of traditionally underserved individuals or communities or targeted lending activities (Community Investing).

In 2020, ESG integration was the most adopted strategy worldwide to select and invest in sustainable assets, followed by negative or exclusionary screening, corporate engagement and shareholder action, norms-based screening, positive and best-in-class screening, sustainability-themed investing, and impact investing.

In the USA, ESG integration and hostile or exclusive screening were the most popular adopted strategies in 2020. In Europe, negative or exclusive screening, corporate engagement, and shareholder action were the most popular adopted strategies during the same period.

Sustainable Investment-Facts & Figure

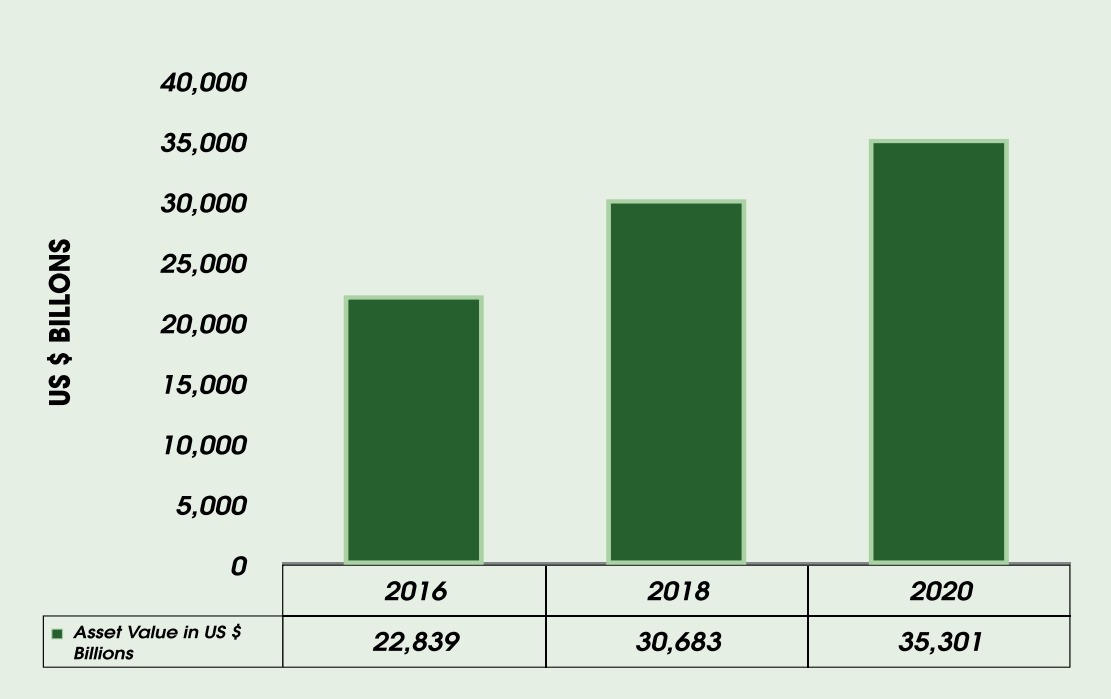

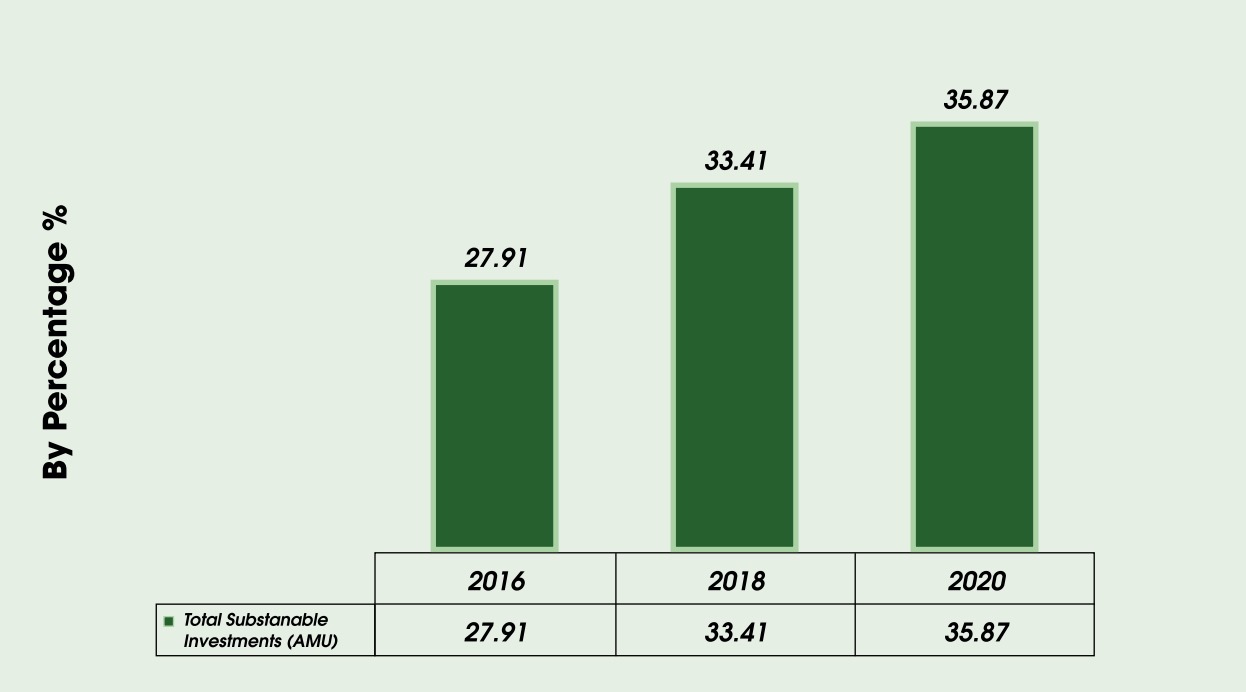

Over the years, sustainable investment in the economy has grown manifold. As of 2020, the value of global sustainable investment stands at $35.3 trillion, and it has grown by approximately 55% between 2016 and 2020.

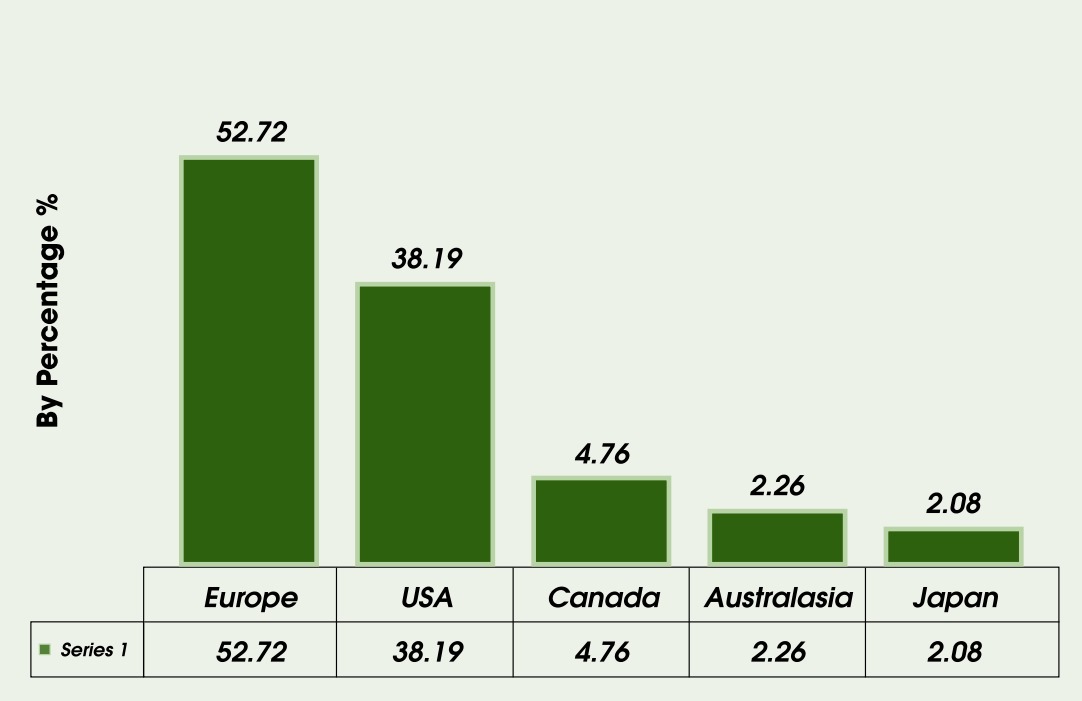

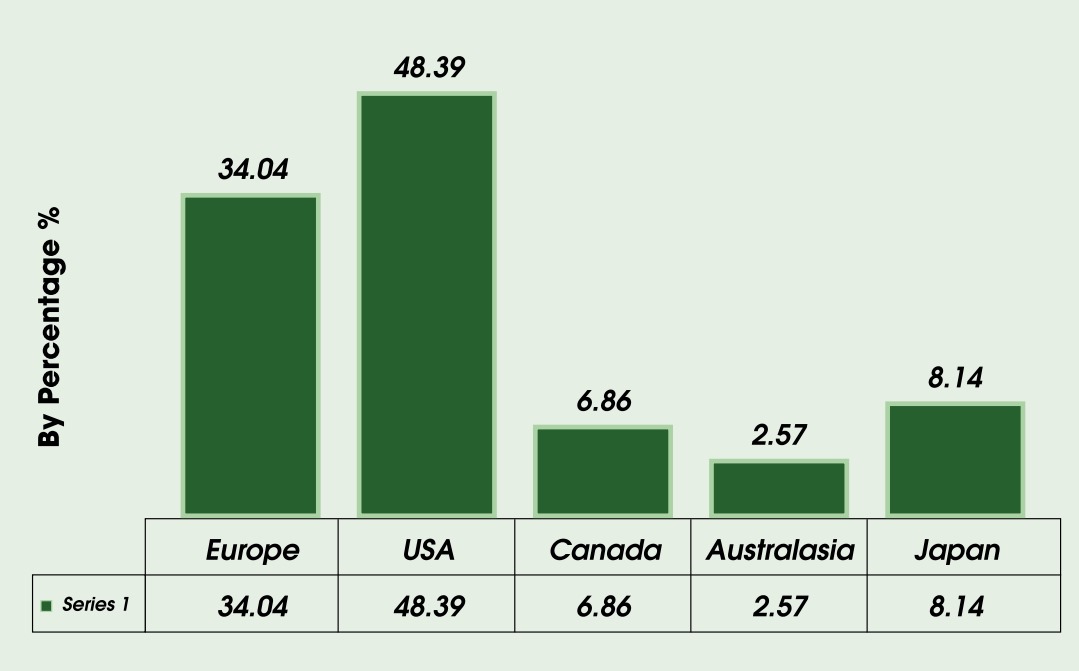

In 2016, Europe had the highest proportion of investment in sustainable investment, followed by the USA, Canada, Australasia, and Japan. In 2020, the USA overtook the rest of the regions, followed by Europe, Japan, Canada, and Australasia.

Overall, the USA and Europe constituted 80% of global sustainable investing assets between 2018-2020.

Figure 6: Growth in value of Sustainable Investment

Figure-7: Sustainable Investment by Region (by percentage)

Figure 8: Sustainable Investment in 2020 by Region (by Percentage)

The proportion of sustainable investment in the total ‘Assets Under Management’ (AMU) category grew by 54 % between 2016 and 2020, aligning with this trend.

Figure 9: Proportion of Sustainable Investments in the Total “Asset Under Management” (AMU) category (by percentage)

The global trend suggests sustainable debt instruments (Green, Sustainability, Social, Sustainability-linked bonds, and transitions) are used to invest in renewable energy, carbon neutrality, solar, environmental, water, green innovation, sustainable awareness, SDGs, positive impact, socially responsible investing, affordable housing, education, gender equality, SDG housing, youth, employment, blue transitions, green transitions, and low-carbon transitions health care, SDG housing, youth, employment, blue transitions, green transitions, and low-carbon transitions.

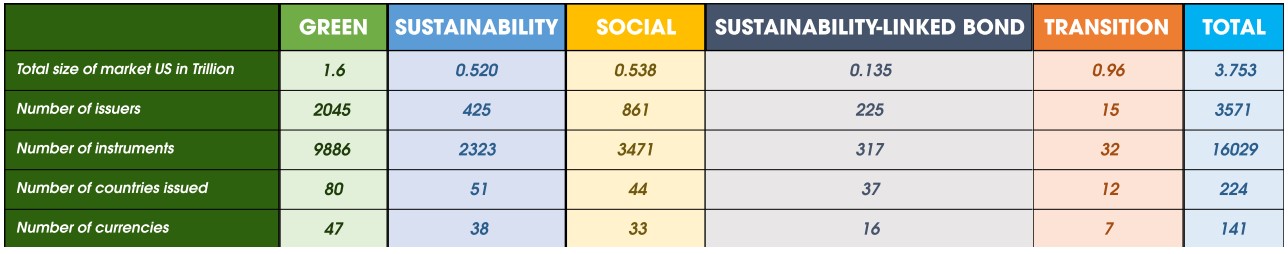

Table 2 Components of Sustainable Debt Instruments

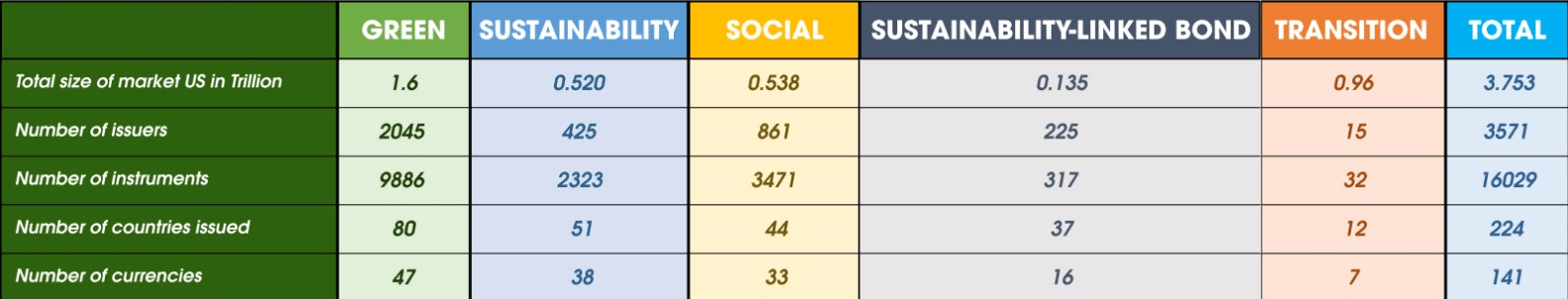

As of 2021, Green bonds are the most significant sustainable debt instrument in terms of financial value, and they account for about 43% of the total USD 3.75 trillion sustainable debt market, followed by social, sustainability, sustainability-linked bonds, and transition bonds. Green bonds are also the primary debt instrument in terms of the number of issuers, number of instruments, number of countries of issue, and the number of currencies issued.

Table 3 Size of Sustainable Debt Instruments in 2021

The longitudinal trend between 2015 and 2021 suggests that most green bonds are generated from Europe. Supranational and Latin America are significant sustainability issuers of debts. Europe is a primary source of Social Bonds; 88% of Non-financial corporations issue Sustainability bonds, and lastly, Europe and Asia-Pacific are major issues of transition bonds.

Most sustainable debt instruments are issued in Euro or USD with a maturity tenor of 5 to 10 years. The USA and China are the issuers of green bonds, while France is the major issuing country for social bonds, and Italy leads in issuing sustainability-linked bonds. The Chilean government is the only sovereign country in the world that issues green, social, and sustainability-linked sustainable debt.

Over the decades, sustainable finance has grown steadily; however, developing sustainable taxonomies in each jurisdiction is essential to provide clarity and guidance to the financial markets in which economic activities and investment assets can be termed sustainable

investment and to avoid camouflage or greenwashing.

The EU, Russia, China, and ASEAN countries have a sustainable taxonomy in this context.

The UK and South Africa have draft taxonomies, while Canada, India, Brazil, New Zealand, and Chile are developing such taxonomies. Lastly, Australia and Mexico are at the discussion stage of such development.

Table 4 Characteristics of Sustainable Debt Markets (2015-2021)

Today’s world is at the crossroads of challenges and opportunities. We are more than halfway into implementing the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. In addition, we are also committed to comply with the Paris Agreement by 2030. However, as the world economy has been hit by two back-to-back events, such as the global pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine military conflict, the global effort for advancing sustainable development, including the determination to fight against climate change, has also faced a setback.

Many countries are experiencing primary food and energy crises due to high inflation following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and, at the same time, the conflict has also triggered a surge in demand for coal. Both dimensions of development have become paramount, and sustainable finance is even more necessary than before to support greener, inclusive, and resilient economic development.